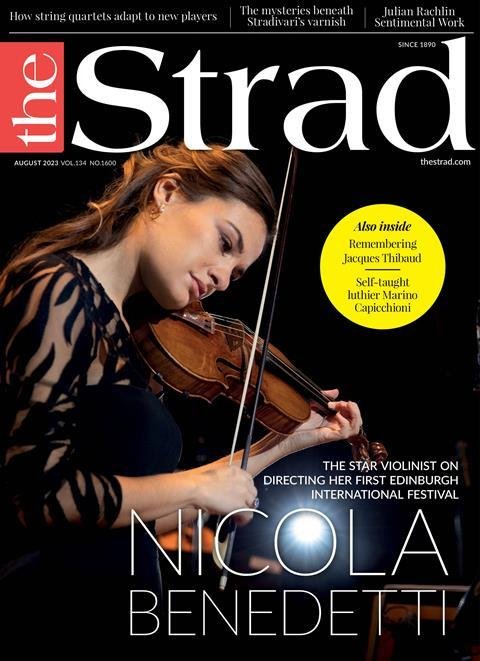

Nicola Benedetti featured on the cover of The Strad Magazine

Introducing the August 2023 issue of The Strad featuring Nicola Benedetti

Only 36, Nicola Benedetti is making her much-anticipated debut as director of the Edinburgh International Festival this year – the first Scot, woman and violinist to occupy the position. She speaks to Rebecca Franks about her plans.

The Strad

August 2023

Nicola Benedetti is tired. ‘Honestly, extremely tired right now.’ I’m not surprised. The Scottish superstar, 36, is talking to me straight after a rehearsal for Mark Simpson’s Violin Concerto, a vastly demanding piece written during the pandemic that bursts with emotion and virtuosity. ‘It’s just so full on,’ she says over the phone from Cologne, having barely had time to put away her violin. ‘It’s an exhausting work. But for all the right reasons. It’s so full of heart and soul.’ Yet giving the German premiere of this modern classic is par for the course for Benedetti, one of the world’s leading violinists, who gives everything to the music and causes she believes in. The real reason she’s feeling in need of rest is something else entirely: Benedetti has just launched her first season as director of the Edinburgh International Festival (EIF).

Benedetti at the 2023 Edinburgh International Festival launch

Photo: Mihaela Bodlovic

What with interviews, photo calls and media briefings, it’s been a busy week – and it’s small wonder the press has been clamouring to speak to her. Benedetti is both the first woman and the first Scot to hold this post at the heart of the UK’s cultural scene – and readers of The Strad will no doubt be delighted to know that she’s also the first violinist in the role. ‘I think these moments are symbolically poignant and have meaning that goes far beyond you personally. That’s an extremely positive thing,’ she tells me. ‘There’s so much for me to learn from those who have taken on this role before me, and I try to look upon that with as much curiosity and humility as possible. But at the same time, I can’t help having a different perspective, both being from Scotland and being female. I think it’s OK to lean into that.’

Her first festival this August makes a bold statement. ‘Where do we go from here?’ is the question stamped in punchy yellow letters on the black cover of the EIF’s season guide. The words come from the 1967 book Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? by the American civil rights leader Dr Martin Luther King, Jr. ‘I’ve been an avid follower and massively interested in his work for a long time, and I had this book at home – but I did a full reread,’ she tells me. As she explains in her eloquent programme foreword, ‘I am moved by the power and urgency of his mission, philosophy of non-violence, fierce compassion, and uncompromising internationalism in the face of brutality, irrational hatred, and closed-minded certitude.’

Of course, translating words and themes into an arts festival, built around live programming across music, theatre and dance, is no simple task, even when drawing on someone as powerfully inspiring as King. ‘You’re trying to balance what is entertainment, a feeling of pulling people together around something that’s uplifting or fun, with a deeper purpose that has a weight to it,’ says Benedetti. ‘You look at what is the highest potential in terms of what a festival offers to people in their everyday lives. Festivals have served a lot of different purposes, but at their heart they are about people coming together, community and a sense of elevating one another around something.’

The EIF, which was founded in 1947 and celebrated its 75th anniversary last year under the direction of Fergus Linehan, came into being, Benedetti points out, after ‘one of the most harrowing, weighted, serious and challenging periods of British history’. There are parallels, perhaps, with the recent turbulent period blighted by Covid-19, the war in Ukraine and a cost-of-living crisis. Was Benedetti drawn to ask ‘where do we go from here?’ because times are bleak? ‘I think the fact of it being a question allows people to take it how they see fit. And that’s part of the excitement for me: it can create activity and dialogue around something that’s otherwise a bit static and not interactive,’ she says. ‘Crux points exist all the time; it’s up to us to pull them into focus. We’re choosing to look at this moment as a crossroads.

Photo: Andy Gotts

‘A few close colleagues expressed a concern around the title showing vulnerability or an insecurity around decisiveness and direction, but that’s not how I function. I always perceive that the best in people comes from them being part of a cycle of interaction, and you get a better sense of yourself through that friction and interaction,’ she continues. ‘It’s very deliberately trying to invite more conversation.’

In this spirit, Benedetti has invited her first cohort of festival guests – two thousand performers from 48 countries – to respond to three ‘invitations’: community over chaos; hope in the face of adversity; a perspective that’s not one’s own. The classical music thread, which features an abundance of string quartets and chamber groups, as well as recitals from singers, pianists and so forth, is built around orchestral residencies from three of the world’s great orchestras: the Budapest Festival Orchestra, the LSO and the Simón Bolívar Symphony Orchestra. ‘They were deliberately chosen to correspond with the three thematic invitations of the festival, says Benedetti. ‘Conductor Iván Fischer set up his Budapest orchestra with a very specific mandate: to serve community and to keep alive the purpose and reason for being an orchestra. They’re forever questioning, forever evolving. I think it has to be one of the most significant examples of what it’s possible for an orchestra to do in that regard.

And then you have the London Symphony Orchestra. For me, it’s always been an orchestra that represents the most edge-of-your-seat risk-taking and intense performances,’ she says – and she should know. Benedetti regularly performs with the LSO (and in 2021, in a live-streamed, socially distanced performance, premiered the Simpson Concerto with the ensemble). ‘If you look at who the musicians have chosen as concertmasters and conductors, they are very bold, brave and unique personalities. Their whole residency occupies this space of wildly ambitious and hefty, existential, extreme works.’ The orchestra’s residency ends this year with Messiaen’s Turangalîla Symphonie, described by the EIF as a ‘profound cry of relief at the end of the Second World War’, epitomising hope in the face of adversity.

’The Simón Bolívar Symphony Orchestra’s repertoire is a mix of some South American works and more standard European fare,’ she says. ‘It’s also about what they represent from a more philosophical standpoint, and they come from a part of the world very different from where a lot of the orchestras we invite come from.’ The Venezuelan orchestra has a special connection with Scotland and Benedetti. Not long after the ensemble made its high-energy debut at the BBC Proms and the EIF in 2007, Big Noise was launched on the Raploch estate in Stirling. Just as the Sistema programme back in Venezuela has given a free music education to deprived children, this new project put instruments and tuition in the hands of primary school pupils.

In the years since, the scheme has been a success, and it now runs in six communities – and Benedetti is ‘Big Sister’ and board member of Big Noise and Sistema Scotland. Yet the original El Sistema in Venezuela has faced strong criticism, including accusations of bullying and corruption. ‘I’ve seen commentary on the controversy of bringing them, and having been on the board of Sistema Scotland, I have been party to a huge amount of their criticism from the inside,’ she says. ‘But I absolutely, fundamentally disagree with not inviting an orchestra like that because of the controversies. They’re connected to us nationally. I’m thrilled and proud that they’re coming.’

Performing Mark Simpson’s Violin Concerto with the LSO at the Barbican in 2021

Photo: Mark Allan

With her Ayrshire roots, Benedetti might have been tempted to lean into the Scottish identity of the EIF, but the sheer range of the programme finds her looking outwards, encompassing as it does Korean theatre, Belgian puppet and mime artists, African dancers performing Pina Bausch’s choreography for Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, and the Aga Khan Master Musicians’ exploration of the Silk Road. ‘The “international” element is like two streams that run together,’ she says. ‘One is the absolute, colossal diversity that exists around the world, which is so beautiful in its colourfulness and in how different people can be and how many directions they can take you in. But the undercurrent stream is the one that binds us all: it’s identical through life, geography and time – those basic experiences that we all feel similarly about the world over.’ She continues: ‘That’s where you can take your audiences on a tale of connection and commonality across the world. A lot of that is in choice of programming, repertoire and artists, but it’s also in how you reveal and tell the story of the festival as the people walk through it. That’s something we’re not really going to be able to achieve this summer in the way that I’m conceiving of it. It’s too much to do in too short a time. But we will expand on that in years to come.

When Benedetti talks about the festival, her passion is evident. It’s a landmark appointment for Edinburgh – but it marks a new personal chapter in the violinist’s career too. She’s been at the front of her field since the age of eight, when she led the National Children’s Orchestra of Great Britain. At 16, she won the BBC Young Musician of the Year competition, signing a deal reportedly then worth £1m with Decca Records, for whom she still records exclusively. She has toured the world as a violinist, selling out concert halls, making chart-topping albums, winning awards and being made a CBE. In 2019, she took her long-standing commitment to music education a step further when she launched the Benedetti Foundation, which has since worked with more than 50,000 participants in its mission to provide equal access to music participation and appreciation for all. It runs online masterclasses and in-person sessions, offering education and inspiration.

’Big Sister’ Benedetti with children from the Big Noise initiative in Govanhill, Scotland, in 2019

Photo courtesy of Sistema Scotland

Benedetti’s EIF role is, arguably, simply a high-profile, demanding extension of an already high-profile, demanding career. It’s another avenue for her to spread her belief in the power of music to improve lives. Yet the idea of stepping into management came as a shock to Benedetti, even though she had grown up in the business world, thanks to her Italian father, an entrepreneur and self-made millionaire. ‘It took me a long time to get my head round the notion of this being a possibility for me personally. I really hadn’t considered taking on such a thing,’ she says. ‘But the process of applying is lengthy, complex and thorough so it gives plenty of opportunity not only for them to see whether you could be right for the role but also for you, the applicant, to see if it’s something you feel confident and comfortable in. That was an extremely useful process for me.’

It’s evident that her career has stood Benedetti in good stead for the challenge. ‘I’ve produced my own tours, put on concerts and galvanised people around something they thought couldn’t be done,’ she explains. ‘I would say that I can conceive of something and then convince other people about the idea. The biggest challenge for me is to get comfortable with all the areas of expectation around the job that are not my forte or expertise or experience. I had to ensure that it was all bolstered by the right people.’ And ideas were never an issue: ‘The main challenge was to declutter and channel the many notes I had made – it was 50 pages of writing of my thoughts that had accumulated over a few months. I had to organise, prioritise and present them to the board and staff in a way that was comprehensible.’ One example: ‘I had 40 different chamber music pieces that I definitely wanted,’ she says, laughing. ‘I had to be reined in – obviously that’s not realistic. But Andrew Moore, our head of music, is so knowledgeable about who’s out there on the scene, so it was a case of discussions between the two of us.’

When her appointment was announced, some media commentators wondered how Benedetti would juggle the demands of her performing career and foundation with those of directing an international festival. ‘One main task for any international festival director is getting to know about fresh and exciting work in theatre, dance and music across the world,’ stated Richard Morrison, chief culture writer at The Times. ‘I don’t doubt that Benedetti will bring a keen critical eye to that job, but the question is whether she can find the time to do it properly,’ he wrote. Benedetti admits that there have been some challenging moments: ‘How tired I am right now is an example – but look, that was always going to be the case. I don’t think there’s anything terribly surprising on that front. The whole experience, though, is definitely weighted towards being exhilarating, exciting and wonderful.’

One big decision Benedetti has made for the first year is that she herself won’t be performing in any of the main concerts, although she will be grabbing her fiddle to open the Hub, a space for audiences and artists to mingle and for less formal music making. She’ll also be playing as part of the opening celebration weekend. ‘I think playing near the beginning will actually help me in a way, because it requires such a specific kind of focus. I just hope I’m able to pace myself and my excitement,’ she says. And audiences will find her flexing her presenter muscles, exploring subjects like the future of the orchestra with Iván Fischer, contemporary classical works with presenter Tom Service and the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, and the epic Turangalîla Symphonie with Simon Rattle.

In the meantime, Benedetti has plenty of her own performances to enjoy. Between June and August, she has two concertos in her sights. One is Beethoven’s ‘Triple’ Concerto with two other former BBC Young Musician stars, cellist Sheku Kanneh-Mason and pianist Benjamin Grosvenor, and the Philharmonia. The other is Wynton Marsalis’s Violin Concerto (2015). The American jazz trumpeter and composer wrote the 40-minute piece for her, along with the Fiddle Dance Suite (2018), and Benedetti has championed both ever since in concert and on disc. ‘I’ve played the Marsalis countless times, and I did it at the Proms last year, so it’s well in my fingers,’ she says, as she contemplates her upcoming performances of it in Canada and France. ‘It’s a world unto itself – and it’s always an amazing experience playing that piece.

‘I don’t want a violin concerto that I find easy to play. My relationship to playing a concerto is not based on ease at all. I want it to feel like I’m climbing a mountain every time I walk on stage.’ She might be talking about concertos, but hidden in her statement, I suspect, is the real clue as to why Benedetti has taken on the EIF. While others might have happily basked in the concert applause and rested on their considerable laurels, Benedetti knows that nothing worth having ever comes easy. I don’t think she’d want it if it did.

Read the full article here.